- Home

- Meena Kandasamy

When I Hit You Page 6

When I Hit You Read online

Page 6

When I hit you,

Comrade Lenin weeps.

I cry, he chronicles. The institution of marriage creates its own division of labour.

VI

I folded the clothes,

arranged them in the almirah,

dimmed the lights,

straightened the bedspread,

placed the two pillows side-by-side

and wore the nightie.

In front of my thirst lies

the forbidden drink of night;

with dreams that relish many tastes,

my sleep loiters outside the room.

ANAR, ‘SLEEP LOITERING OUTSIDE THE ROOM’

The common, widely held opinion is that writers dig the ruins, scour the past, always put themselves there. Yes. But at strange times they put themselves elsewhere. My husband is railing at me, slapping me, throwing my laptop across the small kitchen, forcing me to delete a manuscript, a non-fiction book-in-progress, because somewhere in its pages there is a mention of the word lover. He accuses me of carrying my past into our present, and this treason is evidence enough that there is no hope or space for the future to flourish. At this point I am not listening to him. I have no intention of responding. I am thinking of being at a point in the future when I would be writing about this moment, about this fight, about the stinging slaps that mark my cheeks and only stop when I have deleted what I have written, about how I am forced into arguing about freedom of expression with the man I have married, about the man I have married with whom it has finally come to this, to this argument about the freedom of expression. And I am thinking of how I am someday going to be writing all this out and I am conscious that I am thinking about this and not about the moment, and I know that I have already escaped the present and that gives me hope, I just have to wait for this to end and I can write again, and I know that because I am going to be writing about this, I know that this is going to end.

* *

What does my husband know of love? Does deleting an email, a book-in-progress, a random user-generated reference on Wikipedia, the history of all the Bluetooth devices my phone has paired up with, delete what I have felt for someone? If the material does not exist, does the memory go away as well?

* *

I write letters to lovers I have never seen, or heard, to lovers who do not exist, to lovers I invent on a lonely morning. Open a file, write a paragraph or a page, erase before lunch. The sheer pleasure of being able to write something that my husband can never access. The revenge in writing the word lover, again and again and again. The knowledge that I can do it, that I can get away with doing it. The defiance, the spite. The eagerness to rub salt on his wounded pride, to reclaim my space, my right to write.

* *

LETTER TO A LOVER

This is not a typical love letter. I give you no news of sparrows that I spy perched outside my window, no anecdotes of the vicious fight I witnessed between two nuns who walked past my home. Today, as I begin to write to you, I want to write with gravitas, to write about things that are beyond me, beyond you, too.

I wonder how an opportunist like my husband managed to make inroads into a political party that I have always respected; how he succeeded in hoodwinking the leadership at every stage, how he came to be what he is today. For all its celebration of introspection and self-criticism, how could they not have seen him for what he is? Were they relaxed with what they saw, did they wash it all away as patriarchal, feudal tendencies that are inevitable in someone coming from a small village? Did they not notice his attitude towards women – were they fine with it, did they try to censure him, or did they themselves share the same kind of nervousness and disdain towards feminists? Was respect and love something that the radical only reserved for women who were gun-toting rebels, women who attended and applauded at every party meeting, women who distributed pamphlets and designed placards? How did these women survive these violent, aggressive men in their ranks? Did they walk out? Did they fight? Did they leave their sexuality behind or did they barter it to make life in the organization easier?

I fell in love with the man I married because when he spoke about the revolution it seemed more intense than any poetry, more moving than any beauty. I’m no longer convinced. For every genuine revolutionary in the ranks, there is a careerist, a wife-beater, an opportunist, a manipulator, an infiltrator, a go-getter, an ass-licker, an alcoholic and a dopehead. For every militant fighter who dies on the front-line, a fraud comes and claims the slain man’s greatness. For every original thinker, the parrot in the ranks who claims the wisdom as his own. Parties build themselves on the shoulders of real heroes, nurture themselves on their bloodshed, even as the imposters make merry.

That is why I yearn for you.

You, without any masquerade. You, without any glorious struggle in front of you. You, just shining in your own light, dwelling in your own darkness, you, with no grand zeal. You, with only your words, and no highfalutin theory. You, who told me on a rainy morning that when you were dead you wanted to be buried in my hair. The same you, who married another girl three years later. You, with all your contradictions, you, who do not make promises, you, who do not judge. You are real, and now, I need your realness.

* *

LETTER TO A LOVER

I write to you because I can. I do not have something concrete to say. Today is one of those days without a single new thought. Everything I think about, in the end, somehow winds up back at my marriage. The oppressive heat, the ups and downs of the roads, the sugarcane that’s crushed like long, breaking bones to yield the sweetest juice, stories one hears of moral police bullying teenagers in town, the deceptive orange of the local curries. All of it becomes metaphor.

I set out to write to you about something far removed from what is going on with me. I fail. I think my state is the textbook case of a trap: when you are inside a trap, thinking about other things sets you free. Simultaneously, everything that you think about reminds you of your own state of entrapment.

When something is too obvious, I think the best course of action is to pretend not to notice it at all.

* *

LETTER TO A LOVER

You know, dear love, as well as I do, that it is difficult to stay within the frame of language and not feel desire. Sexual play is endless in ancient languages. Words are constantly weighted with the meanings they carry.

Isn’t that why conversations with lovers are a constant slow tease? To flirt is to give a fresh twist to each word. I make you my own by building a little hut inside each of the words that you use, and staying with you there to watch the sunsets. When you talk of shaving your three-day beard, I whisper to you how my skin smarts with the sudden sensation of being grazed. I imbue the word kiss with the idea of clandestine; I smuggle the thought of me into the word caress. You can never dislodge me from each of the words I’ve meticulously occupied.

Marriage has ruined my romanticism, by teaching me that this thing of beauty can be made crude. Bitch. Whore. Slut. And yet, for every insult that has been flung in my face, language retains its charm.

English makes me a lover, a beloved, a poet. Tamil makes me a word huntress, it makes me a love goddess.

There is a linguistic theory that the structures of languages determine the mode of thought and behaviour of the cultures in which they are spoken. In an effort to understand my life at the moment, I have come up with its far-fetched corollary, a distant cousin of this theory: I think what you know in a language shows who you are in relation to that language. Not an instance of language shaping your worldview, but its obtuse inverse, where your worldview shapes what parts of the language you pick up. Not just: your language makes you, your language holds you prisoner to a particular way of looking at the world. But also: who you are determines what language you inhabit, the prison-house of your existence permits you only to access and wield some parts of a language.

Now in Mangalore, I know the Kannada words eshtu: how much; haalu: milk; anda: eggs;

namaskaram: greetings; neerulli: onion; hendathi: wife; illi: here; ahdu: that one; illa: no; saaku: enough; naanu nandigudda hogabekku: I want to go to Nandigudda.

I can dig out every single word that I’ve uttered in Kannada. In this language, I am nothing except a housewife.

* *

LETTER TO A LOVER

Afternoons are the most unbearable time in my life as a wife. They sprawl out and fill me with dread. I have to anticipate his arrival. I have to show him solid proof that I have been busy. I am lost in restlessness, lost in time that I cannot will away, that I cannot spend. The minutes swell into formless monsters.

Afternoons are beginning to carry in their silence and their stillness the whispered suggestion of suicide. Do it now. It will not hurt. It will be over before you realize. A part of me is surprised to find that, after only a handful of months, I am having to play with this thought, and then, spending the rest of the time trying to fight it. I swing on a pendulum of choice. Alive. Dead. Dead. Alive. Alive. Dead. Dead. Dead. I do not know if I’m alive now. This is the kind of alive that feels dead.

And then again, there are the dead who feel alive.

A hundred yards from where I live lies the Nandigudda cemetery. When the ghosts rise and decide to stop at the first home they encounter for a glass of water, it is my door on which they knock. In the beginning, I refused them entry, but now I have allowed them in.

The most regular visitors are the plaintive four, who were all at various points Mrs ‘Cyanide’ Mohan. When they appear, there is no trace of their features. Each of them eloped with the same man because he promised marriage. Each of them was presented with a special powder meant for birth control. Each of them was found dead in the toilets of public bus-stands or hotels. Each of their bodies went unclaimed by parents who had no idea of the whereabouts of their daughter. Twenty, or even more women fell prey to Mohan’s charms before the police begin to connect the dots. Four of them, after lying lonely at the mortuary in Mangalore, were brought to Nandigudda for their last rites. Now, they visit me, a newly-wed like them. Who, like them, rushed into marriage. A different man, a different terror, and yet, something makes them come to me. Curiosity, perhaps. Although they all met the same end, they are jealous wives, they do not talk to each other. I know this for a fact.

* *

LETTER TO A LOVER

When I am in bed with my husband, I have learnt to be still and silent. Meditative even. Control yourself, he tells me, not in the voice of a lover who does not want to wake his neighbour, but in the voice of an angry teacher. I become the woman of Indian cinema: on the screen this holy act of marital sex is shown through my bangled hand clenching the bedsheet, and this clenching will be sudden, so that it can signal to the viewer that he has taken me in a single thrust. The Tarantino among Tamil film-makers can instead choose to show this by a close-up of my toes that curl and hold still. Otherwise sex itself will elicit no noise, and no other movement from the woman.

So much of sex is what it is because you are allowed to be yourself. This individuality – which can be anything in a lover: fierceness, clumsiness, coyness – is what makes sex different every time, this is what changes the nature of pleasure from one act to the next, from one lover to another. To play the role of the still, passive and submissive woman day after day leaves a woman in a relationship with the ceiling, not with her man. My husband lacks this kind of basic knowledge because Marx and Lenin and Mao have not explicitly written this down, and the declassing classes do not address the sexual pleasure of comrades.

I think about you and me. One of those noisy days, hotel staff in the corridor, and our first time together. You, the man who is not silencing me, shutting me up, letting me shout. For a second that will be everything I want from this world. A moon landing of sorts. As if I finally have the permit to be myself. Like someone stamping my passport and saying, yes, you are free to visit this land, free to shout all you can, all you want. I am not sure we have met. I do not think you know that I exist.

Trust me, love, you will.

* *

As I write to my unseen, as yet undiscovered lovers, the words of my One True Love come to me. His words, with the cadences of his persuasive public speeches, smuggle me back into his arms.

My heart is on a hartal today: no traffic, everything is suspended, all shutters are down, people are staying within their homes. Only you have the unwritten permission to stroll my streets, you can dance if you wanted and sing if you cared, but love, you do not even open your window to look at me. Somewhere in the middle of this, buses are being torched, showroom windows are being shattered, police are being pressed into action, there are slogans and banners and marches, but nothing ruffles you. I make all the noise in the world, but I am alone.

You do not send me messages, not even the fragments of poems, you do not ask if I am alive. I miss you. To see if I can catch your scent, or spot the silhouette of anyone who reminds me of you, I open a window. From where I am, I do not see people, I see the sky and I watch clouds build bridges with one another – they are huge, they are slow-moving in this crude summer – but they manage to get together quicker than we do. I shut the window in disappointment, I turn the lights out, but you do not come to me. You leave me to my loneliness. You are cruel. I lie in wait for you. There is only stillness, a silence fractured by the music I turn on from time to time. I am patient, I look for the smallest sign of you. Instead, I grow old waiting for you. You, who said to me that love was like adoption, have abandoned me.

I could take my life and you would only come to know of it from the evening news, or tomorrow’s papers. I could mutilate myself, and bleed, and you would not even know, you will not weep because you do not know, you will not plead with me to stop because you do not know, you will not hold my hand with your nervous fingers, you will not comfort me with your kisses, you will not burst into tears as you see me hurting; nothing will happen because you are elsewhere, my love.

I am at home, lying down on my marital bed and this is how I sin. Memory transcribing the words of a love from long ago. This will be a thought-crime in my husband’s eyes. I do not feel any guilt. I do not think any of his beatings or belt lashings will cause me to feel any guilt. With me, at this moment, I feel only the relish of rebellion, the comfort of long-forgotten words that now make me feel safe, feel loved.

* *

LETTER TO A LOVER

How do I want you to imagine me as I write this to you? Not as a woman with shining eyes furiously typing away something on a laptop, a something which she will erase as evening begins to stalk her doorstep. That’s the image of a wife as a writer, but I’m not a writer except in these brief snatches of time. So, you now mentally recompose the scene of me. But please don’t choose one of a battered wife – that’s an image that will brand itself on your mind, and the longer you think of it, the more impossible it will become for you to relate to me, to love me naturally. You will then love me like a scar loves a wound and I deserve something more.

For now, imagine me in this kitchen. The kitchen is the tiniest space in our house, but it is a space of peace. While everything about me drives him into fits of rage, it is my food that manages to placate him. It is the only redeemable thing that he finds in me. This is the something on which I can try to build, try to trick myself into the make-believe of a happy marriage. In the kitchen, I discover my mustard-grain of faith. The only ceasefire comes from the food I make. The only conversations we have where he does not begin to suspect me are when we are talking about meals. Were you to tell this story, shoot this as a culinary Bildungsroman. Include flashbacks to pine forests and orange plantations. Choose a tall, lanky thirty-year-old to play the role of a Naxalite guerrilla, struggling to eat a decent meal when he is underground, part of a twelve-member armed squad surviving in inhospitable conditions. After an experience like that, it is understandable why he is particular about taste. That is why he loves my food. Even though he interferes, and lectures me on how to

reduce wastage and how to save cooking time, the kitchen is the only place in which he defers to me. It is the only component of our marriage where I have the upper hand.

Remember, lover, if you ever direct the film of my life, that the food must overshadow the domestic players. The assault on your senses will be the footage of red tomatoes breaking down in the frying pan with green chillies and pink-white onions. The tang of tamarind infusing a chicken curry turns it a rich shade of brown. The stark green of cluster beans interrupted by the brown-black of mustard seeds and the white of roasted, powdered rice. The julienned white insides of a banana stem, soaked in buttermilk, drained and then sautéed with cumin, grated coconut, a pinch of turmeric and red chilli flakes bring to your plate the lush richness of a faraway hometown. The sounds of oil sizzling as sweet-smelling cloves and cinnamon bark and fenugreek and star anise are dropped into the pan one after another. Flying white ants from a monsoon evening will be craftily trapped to make an unexpected evening snack. And here, as all these elaborate banquets are staged, you will see the picture of domestic bliss that my husband is trying hard to forge. You will see how eagerly I step into the shoes of the good housewife.

But I have learnt that food could give away my secrets. I make for my husband only the food I learnt to make from my father. I do not experiment. I do not replicate what I did with my lovers, or what I plan to do with you. Every day, I serve food to him as if it were a declaration of chastity.

* *

LETTER TO A LOVER

Yesterday, I thought about all kinds of men: the thin, the tall, the fair, the swarthy, the agile, the self-possessed and whatever else can be left to my dirty imagination. For three hours last night, I was being held hostage by my husband who sermonized on the role of clothes. ‘When class disappears, the masculine and feminine disappear. Class society gives rise to the concept of shame. When shame disappears, we will all be naked.’

At first, the parade of men filing through my brain was simply a distraction from my tedious husband. But the more he droned on – ‘A classless society will be a nude society. The sexualization of the naked body is a result of market forces.’ – the more I took perverse delight in taking full advantage of those men in my mind.

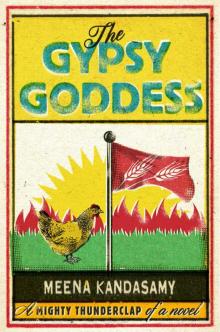

The Gypsy Goddess

The Gypsy Goddess When I Hit You

When I Hit You